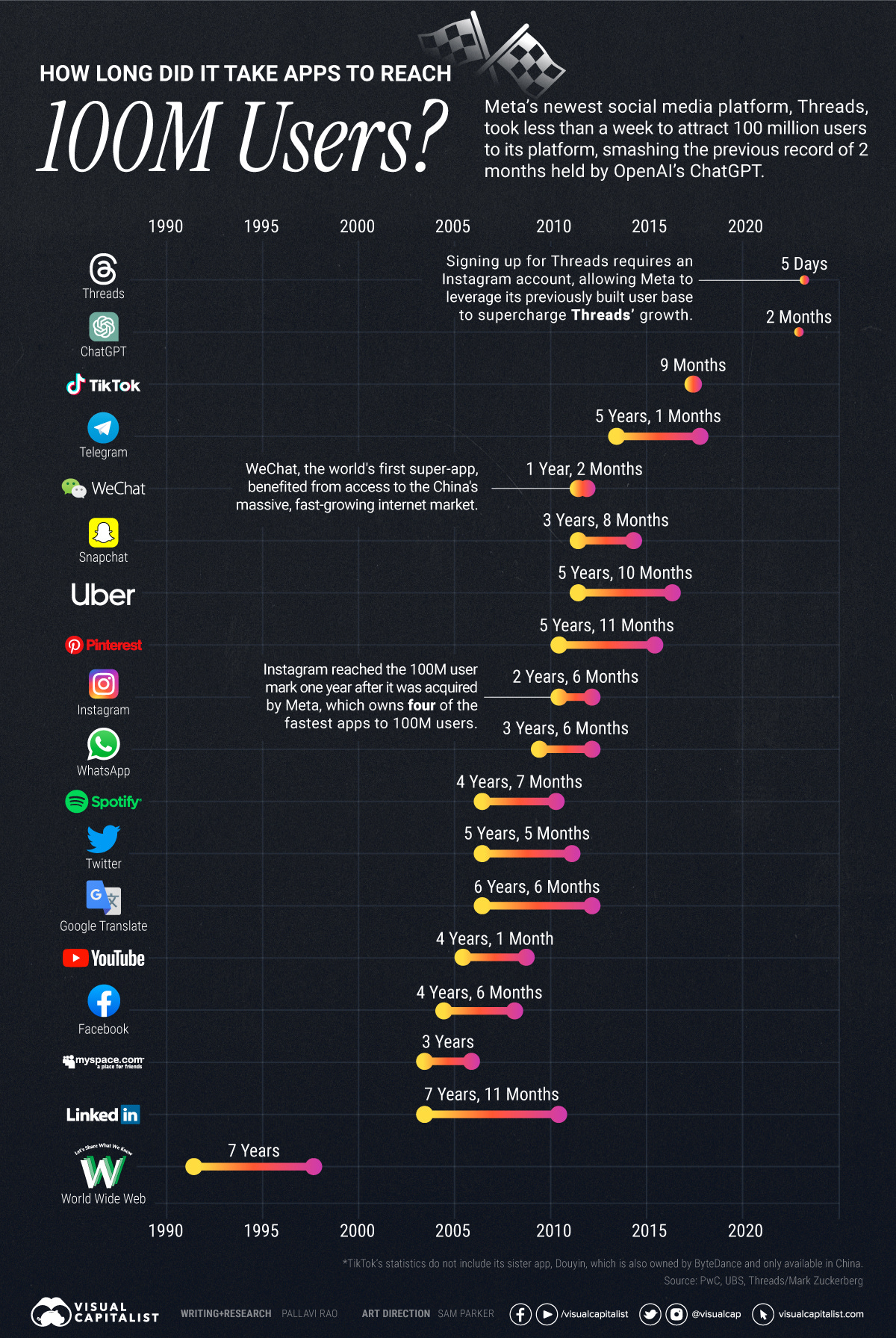

After ChatGPT was announced in late 2022, reports surfaced that management at Google had issued a “code red” in response to the popularity of OpenAI’s new, revolutionary chatbot. The excellent chart below from Visual Capitalist shows that ChatGPT was the second fastest application to reach 100 million users (only after Facebook Threads of 5 days, which arguably isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison given its tight integration with Meta’s existing platforms).

The utility users derive from ChatGPT is vast and significant. Its ability to perform a wide range of personalised tasks makes it far better suited to meeting the needs of internet users compared to the time-consuming process of sifting through a list of links.

The personalised capabilities of ChatGPT and similar LLMs set them apart from traditional search engines and need to be understood. Unlike search engines, which provide a list of links requiring further navigation, LLMs deliver specific, actionable responses. For instance, when asked for a high-protein vegetarian recipe, ChatGPT generates a detailed suggestion on which ingredients to buy, how long to cook each of them, and in what order. If you don’t like a certain food, you can remove it by asking a follow up question. Want to know how many calories are in the recipe? Just ask. Want to know how to increase the portion size to fit 6 people while only being able to use 1 pan, 1 stove and 2 air fryer drawers, ChatGPT has you covered. In complex scenarios, such as managing stress or finding personalised relaxation techniques, ChatGPT provides tailored advice rather than generic search results. Why go to a therapist when ChatGPT can provide you with insightful wisdom at your convenience? Want to create a table of the highest grossing movies since 1990? ChatGPT can do that instantly, saving you hours of combing through lists and data sources. Its versatility extends even further, making it the go-to assistant for countless personalised, real-world needs. All these questions lead to an uncomfortable thought…

…why use Google at all?

There are certain instances where indexing pages through a search engine is appropriate. Filling out an application form on a specific website. Checking the weather. Finding research papers that fit your report. But all of these are simple informational retrieval type questions for which Google Search is optimised, not personalised information structuring that provides greater utility to the end consumer.

Shifting away from Google Search

The business of Alphabet, despite its sprawling corporate structure and numerous side bets, is actually rather simple. The company gets a cut when a user clicks on, or sees, an advertisement on its platform. While Google doesn’t disclose a breakdown of profitability by segment, Google Search comprises an estimated 68% of total revenue (source: Goldman Sachs). Given that this is their most profitable segment too, it is possible that it generates over 80-90% of the company’s operating profit.

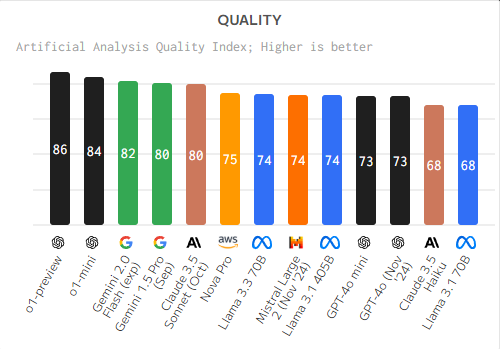

The key rebuttal I hear in response to questions regarding Google’s LLM problem is that they are catching up to OpenAI in the quality of their AI models after their disastrous launch. Firstly, Google’s models are still behind OpenAI (as shown below), although the gap has substantially tightened since launch.

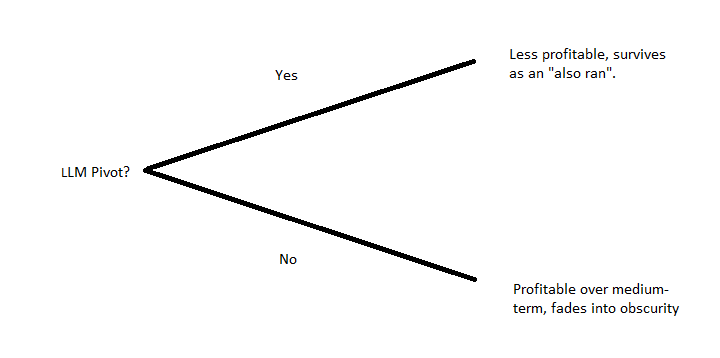

If attention shifts away from traditional search engines towards LLMs, then Google faces two equally poor options. The first, and arguably the best long-term solution, is that Google accepts this new paradigm and is willing to shoot their golden goose (click-through on Google Search) and pivot their flagship product towards Gemini, its LLM offering. The benefit of such action is that Google is able to pivot its vast intellectual capital (and vast capital capital) towards focussing on a new technology that is taking share from its uber-profitable legacy system, where it possessed the best indexing technology for multiple years thanks to Larry & Sergey’s PageRank. The company has had an effective monopoly on internet search for a long time due to the aforementioned algorithm, and has monetised this to great effect (since 2006, Google has increased its operating FCF from $3.5bn to $101.7bn, a 29x increase).

Their period of moat expansion (and investment levels) based off PageRank coincided with the growth in internet usage. In 2006, the company was investing roughly 2x its CFO into the business (to fund its expansion), compared with only 25% in 2023. The operating leverage on these investments has driven significant FCF improvements ever since, and has acted as a cash-cow to fund their more speculative ventures. Some developers argue that Google has over-monetised its Search product leading to a poorer customer experience, but investors have been pleased with Google’s results and awarded the company a $2.39tn valuation (currently comprising 4% of the S&P 500). If Google were to enter the LLM arms-race, it would not have the significant advantage that it currently holds in Search (being subservient to OpenAI’s models in terms of performance), potentially leading to a less favourable earnings multiple from investors, on top of a diminished net profit value. Given most active money manager’s admiration of Google owing to its historic success, alongside the rise of passive solutions in investor’s portfolios, there is a lot of skin that depends on Google Search’s success.

The alternative option for Google is to do nothing. In this scenario, Alphabet continues to extract monopoly profits from its Search business owing to lower reinvestment levels than under the “pivot” scenario, leading to higher FCF generation over the short-run. Over time, market share would be lost to newer rivals who provide an LLM solution. Google would still be able to monetise its dwindling user base, but advertising prices (and volumes) would be lower due to reduced demand as advertisers shift towards LLM providers. Google's strategic inertia could result in a gradual erosion of its competitive edge. Sticking with this “alternative” approach might protect current revenues (and more importantly, FCF), yet it restricts the company's ability to innovate and adapt to emerging technologies and consumer expectations. The reduced attractiveness of its advertising platform could prompt advertisers to seek out platforms that offer personalised targeting capabilities powered by LLMs, thereby affecting Google’s revenue model more significantly.

Consider wider elements of the business. Alphabet reports Google across two different segments; Google Services (majority Search) and Google Cloud Computing (GCP). Even though accountants and investors like to create boxes within which products can be neatly organised, purchasers of services provided by Google see things differently. Consider Google Cloud Computing vs Microsoft Azure. If a company with a significant amount of private data is considering switching over to the cloud, which provider will it choose? The one with an excellent LLM (to leverage data insight) or the one with a mediocre LLM? Who has the greater pricing power? Will this lead to the highest performing companies (and by extension, most profitable) partnering with Microsoft and leaving Alphabet & GCP behind? Switching costs are seen as the key barrier companies cite for not changing their cloud service provider, but having access to more insightful technology may reduce the value of switching costs as a core tenant of the moat, leading to an exodus of existing customers. Investors often fail to appreciate the level of interconnectedness between the two segments as they believe the impact would be confined to the reporting segment containing Search.

What does the market think?

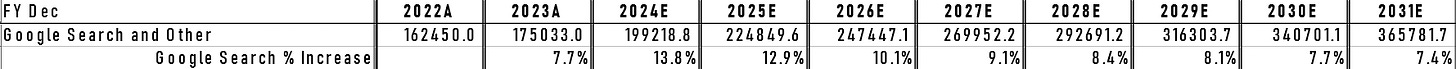

It doesn’t care. Alphabet’s total return (capital appreciation + dividends) is +90% since ChatGPT released on 30th November 2022 (for comparison, Microsoft, who own 49% of OpenAI, has only returned 70% over the same period, albeit at a higher valuation level). It is worrying to see that many investors are still factoring in 2-5x GDP growth for the next 7 years as a base case, showing that the market hasn’t appropriately risk-adjusted their forecasts based on the threat to Alphabet’s level of profitability. I’ve shown below some estimates that believe Search will still be growing at over 7% in FY2031.

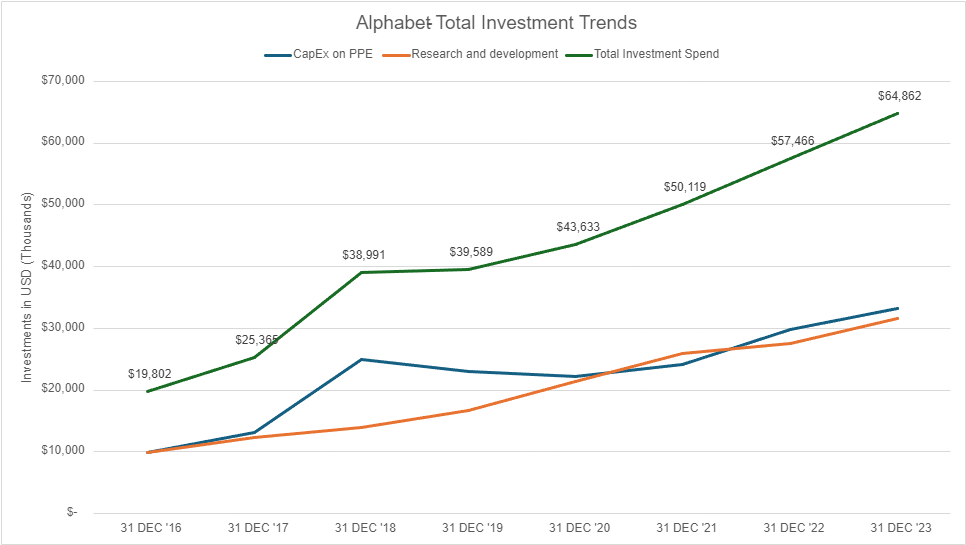

While market penetration analysis suggest the digital advertising market will grow until 2030, it is likely reaching its zenith. Post-2030, it appears that the burgeoning field of large language models (LLMs) will become the principal area of growth as industries explore how to effectively monetise generative AI technologies, for which there are currently many competing approaches. The bullish argument is that the recent re-rating is due to the market positively ascribing greater value to Google’s increasing level of investment as it addresses the LLM problem (illustrated below).

While it is factually correct that Alphabet is investing more heavily in its business, likely to develop competing AI tools, the issue is that this doesn’t coalesce with Google’s current business model, leading to a lower level of profitability in later years. Investment in a business is only as good as the future profit that it will bring, and simply valuing the investment without this consideration is an incorrect approach. In the case of Alphabet, improved profitability is doubtful as LLM generation is expected to be significantly lower margin than search queries. It’s ironic that the seminal “Attention Is All You Need” paper was released, not by OpenAI, but by Google. Corporate historians may one day highlight this event as equally misguided as Kodak's dismissive response to the digital camera.

Conclusion

The shifting dynamics within the tech industry suggests companies must grapple with the integration of LLMs into their business models. Alphabet, with its longstanding dominance in traditional search and advertising, stands at a crossroads. The company's future success may hinge not only on its ability to adapt to this new technological paradigm, but also on how it reconciles these innovations with its existing business strategies. As we witness these developments unfold, it becomes evident that the very innovations Google helped pioneer may now dictate its necessity to evolve, or risk obsolescence. Google’s current position serves as a potent reminder of the relentless pace of technological progress and how yesterday’s winners can very quickly become tomorrow’s losers.

Thank you for reading Google's LLM problem. Please leave your thoughts below.